Where All Light Tends to Go kept popping up in my list of recommendations on Amazon, like those Suggested Friends on Facebook. After seeing it there so many times, I knew I needed to give in and read it. Within just a couple of short days, I had shut the pages and knew that I had to talk to David Joy about this book. Not only is this guy a gifted storyteller, but his passion for other writers and their stories is contagious.

I particularly love how he admits to immersing himself into his storytelling. I think that showcases how much this book means to him and how much it should mean to us!

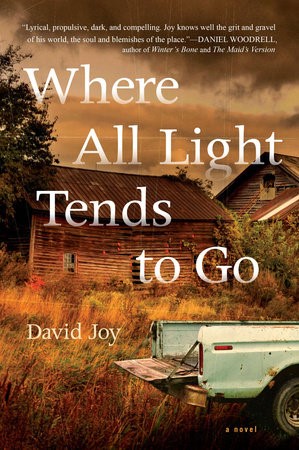

Where All Light Tends to Go is Southern Grit at its finest in this dark debut novel! Joy creates a compelling coming-of-age story about a teen boy growing up in the Appalachian Mountains whose father deals meth in their small town.

The area surrounding Cashiers, North Carolina, is home to people of all kinds, but the world that Jacob McNeely lives in is crueler than most. His father runs a methodically organized meth ring, with local authorities on the dime to turn a blind eye to his dealings. Having dropped out of high school and cut himself off from his peers, Jacob has been working for this father for years, all on the promise that his payday will come eventually. The only joy he finds comes from reuniting with Maggie, his first love, and a girl clearly bound for bigger and better things than their hardscrabble town.

Jacob has always been resigned to play the cards that were dealt him, but when he botches a murder and sets off a trail of escalating violence, he’s faced with a choice: stay and appease his kingpin father, or leave the mountains with the girl he loves. In a place where blood is thicker than water and hope takes a back seat to fate, Jacob wonders if he can muster the strength to rise above the only life he’s ever known.

If only life were that simple. This story is beautifully told and the ending was a strong one, despite the feeling of hopelessness for these people.

Grab your morning cup of coffee and let’s settle in with David Joy, a truly incredible storyteller!

Congratulations on your incredible debut novel! I was so excited to see that it was selected as one of the best books of 2015 by Indigo. How long did it take you to write this beautiful book and what has it been like to have it so well received by so many once it has been released into the world?

The novel started with an image. I was at a friend’s hog lot and I had this image of a young boy standing over a pig he’d killed suddenly realizing how much power he had over life and death. I wrote that scene and I knew that the boy had a story to tell. I kept trying to write that story and I kept getting it wrong, at one point burning about half a novel and starting over. After about a year or so of living with that image I woke up in the middle of the night and I could hear Jacob speaking to me clear as day. At that point it was just a matter of trying to keep up, and I wound up writing the first draft of Where All Light Tends To Go over the course of a few months. That’s kind of a roundabout way of answering your question, but I think I tend to live with images and stories for a long time before I ever actually get it right on the page. Once I’m writing, though, things tend to happen quickly.

The response to the novel has been wonderful. I think the highlight for me has been meeting writers I’ve admired for so long—writers like Daniel Woodrell and Tom Franklin and Donald Ray Pollock and Frank Bill—and actually becoming a part of the conversation.

You refer to your genre of storytelling as Appalachian Noir. What can a reader expect from this genre and if they love this style do you have any other recommendations on books to check out that will fill the void while we await your next novel?

I started using that term, “Appalachian noir,” as a sort of adaptation of something Daniel Woodrell originally used as a subtitle for his novel Give Us A Kiss, his term being “country noir.” He’s sort of the godfather of what I’m trying to do in a lot of ways, along with writers like Larry Brown and William Gay and Ron Rash and Barry Hannah and Harry Crews. As far as what I think folks can expect, these are typically stories about hardscrabble lives, working class people making the best of circumstance. There’s often a criminal element to the story, but I don’t know that that’s a necessity. I think more than that these stories are a balancing act between hope and fate, a sort of tightrope walk above brutality on the one hand and the sentimental on the other. Other writers I admire who write within a similar vein are folks like Mark Powell (The Dark Corner) and Charles Dodd White (A Shelter of Others) and Jamie Kornegay (Soil) and Brian Panowich (Bull Mountain) and Rusty Barnes (Reckoning), or even a novel like Robert Gipe’s Trampoline. Then there are some incredible female writers like Steph Post, who wrote a novel called A Tree Born Crooked, or writers like Bonnie Jo Campbell (American Salvage) and Tawni O’Dell (Back Roads). Some of these writers might not consider what they’re doing noir, but it’s that same type of emotional weight being created and for me that’s the key to what I’m trying to do on the page.

I am going to quote one of my favorite passages from your book. “On the pew where I sat though, there wasn’t a damn bit of light to be had. Light never shined on a man like me and that was certain. In a lot of ways, that made men like Daddy the lucky ones to have only ever known the darkness. Knowing only darkness, a man doesn’t have to get his heart broken in search of the light. I envied him for that.”

The light plays such a big part in this book and we see references to it throughout the story and the title. Why do you think the light (or lack of it) is such an important element in your story and how did you come to create this concept for your readers?

With this novel I knew the title before I wrote the first word. That’s not to say that I knew what it meant, and I certainly didn’t try to write toward that meaning, but rather it just sort of matured with the story. I think that idea of light and dark works really well as a metaphor for what Jacob’s facing. We’ve got an eighteen-year-old kid born into very harsh circumstances that he’s not really equipped to handle. There’s a similar line to the one you’ve quoted where Jacob is talking about the idea of light at the end of the tunnel, that sort of hope that one has when they’re coming out of the darkness. But for Jacob, he can’t understand an idea like that because he’s not coming out, he’s walking into the darkness, and, “for those who move further into darkness the light becomes a thing onto which we can only look back. Looking back slows you down. Looking back destroys focus. Looking back can get you killed.” So Jacob can’t look back. This conflict between light and dark is ultimately about hope. When you’re facing the types of things that Jacob is facing, it’s much easier to just accept the way things are than to hope for anything better. Hope leads to heartbreak and that’s why Jacob’s so conflicted. That’s really the key issue in the book, and so I think that metaphor, the idea of light and dark, helps to stitch that seam.

You have a bit of a Breaking Bad opener with a botched murder situation which was rather gruesome to read and kept me on the edge of my seat. Do you think Jacob’s life would have worked out differently if they had successfully killed the guy?

This is probably the toughest question I’ve ever been asked because what happens to Robbie Douglas is the catalyst for things falling apart. Without that trigger, the pin doesn’t hit the shell. In other words, none of what takes place in the novel would have happened. At the same time, the fatalism that we witness is something that I think was inevitable. If Robbie Douglas had died, Jacob might’ve prolonged that unraveling, but things would have still fallen apart. Lives like Jacob’s typically end one way.

Crime, poverty, and meth addiction create a rather hopeless environment for these characters. Do you think your novel has hope in it? Was it difficult to write in such a sad space or do you feel like you are the type of writer where this dynamic really thrives?

I think there are elements of hope, and I think it’s that balance between hope and fate that, with any luck, keeps the reader invested. As for writing within that space, I can remember after finishing the novel I was talking to my sister and I told her, “It’s going to take a long time to find my way out of the darkness I’ve created.” I’d spent months inside of that space, immersing myself to the point that I was walking into walls, to the point that when I had to go somewhere like the grocery store it felt as if I was moving within a dream. The world I’d created was more real to me at that moment than anything else around me. I think for an artist to create anything meaningful it takes that type of immersion. There’s a sort of sacrifice that has to be made, and, for me, the end justifies the means. I tend to tell stories of heartbreak and circumstance and desperation as I think those types of elements allow you to immediately get to the heart of a character. When things fall apart a person can’t be anything aside from exactly what they are. That’s what interests me most.

Jacob says in one scene, “I’d always hoped she’d become a real mother. But with time, I realized that someone can’t give what they don’t have. She was what she was, an addict, and there was nothing that could be said or done to change her. Death was her only savior.”

I don’t know what to say about that except that it was difficult to watch this dynamic between Jacob and his mother and it made me feel sorry for him to have two parents like this. Is addiction something that you have experienced with anyone close that you channeled in this character?

I really like that you pulled that quote as I think that line, that idea that, “someone can’t give what they don’t have,” is the heart of why she can’t be a mother to Jacob. There are some readers who seem incapable of empathizing with Jacob’s mother and father, but, for me, there are tiny pieces, tiny statements that elude to why these people are the way that they are. That’s really important to me: humanization. Without that I’d just be creating caricatures. There are moments where I think we see what she could have been had she not been addicted to drugs. That’s the reality of addiction. That’s a reality that I’ve seen time and time again where I live and where I grew up. I think the easy thing to do is to dismiss those people, to say, “I’m nothing like that.” The harder thing to do is to look at it with empathy. And empathy doesn’t mean coming to justify those actions as acceptable, but what it does mean is coming to recognize and hopefully understand why.

If there was a sequel, how do you see life working out for Maggie?

I have a really great friend, a mentor and an incredible novelist, Pamela Duncan who ran up to me after finishing the novel and said, “Is Maggie pregnant? She’s pregnant, isn’t she?” I just laughed, but I love this idea of wanting to know what happens to her as I think that’s a good sign that I’ve created a character that resonates. As for what I envision, I think Maggie goes to Wilmington. I think a lot of what Jacob holds as truth as an eighteen-year-old is naïve, but I think what he sees in Maggie, that strength and that certainty that she’ll leave, is real. So, for me, I always saw her getting out.

If you could tell anyone to read one book (other than your own) what would that book be (we list it with all the recommendations over the year HERE)?

I’m going to stay true to my neck of the woods and give you three recommendations—a novel, a memoir, and a book of poetry—from Appalachia because I think a lot of what comes out of this region is tragically overlooked. As far as a novel, everyone needs to read Robert Gipe’s Trampoline. It’s bar none the best debut released this year and it’s arguably the best debut we’ve seen from this region in decades. With memoir, I was really impressed with Leigh Ann Henion’s book, Phenomenal. I think her storytelling is brave and her insight into our relationship with the natural world is matured and beautiful. Last but certainly not least, everyone needs to be reading Rebecca Gayle Howell, especially the poems in Render: An Apocalypse, which are just gritty and raw and lovely. She’s writing scripture. So there’re three for you to get your hands on!

You can connect with David Joy on GoodReads, on Facebook, or through his website! I’m always thankful for these moments with writers and I hope you will pick up this amazing book! You can always connect with me on GoodReads,through our books section of our site, and you can read our entire Sundays With Writers series for more author profiles. Happy reading, friends!

*This post contains affiliate links!

Pin It